Enhancing nanosensor manufacture with a drop of ethanol

Engineers from Macquarie University have developed a technique to make the manufacture of nanosensors less carbon-intensive, more efficient, and more versatile. The researchers have found a way to treat each sensor using a single drop of ethanol instead of the conventional process that involves heating materials to high temperatures. The research findings were published in the Journal of Advanced Functional Materials.

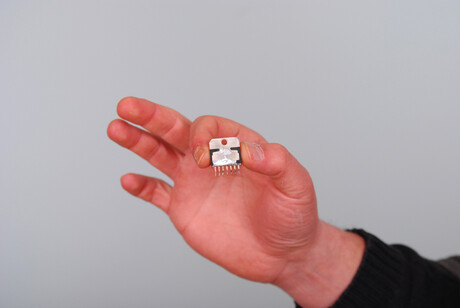

Corresponding author Associate Professor Noushin Nasiri said nanosensors are usually made up of billions of nanoparticles deposited onto a small sensor surface — but most of these sensors don’t work when first fabricated. The nanoparticles assemble themselves into a network held together by weak natural bonds that can leave so many gaps between nanoparticles that they fail to transmit electrical signals, so the sensor won’t function.

Nasiri’s team uncovered the finding while working to improve ultraviolet light sensors. Nanosensors have a sizeable surface-to-volume ratio made up of layers of nanoparticles, making them highly sensitive to the substance they are designed to detect. But most nanosensors don’t work effectively until heated in a time-consuming and energy-intensive 12-hour process using high temperatures to fuse layers of nanoparticles, creating channels that allow electrons to pass through layers so the sensor will function.

“The furnace destroys most polymer-based sensors, and nanosensors containing tiny electrodes, like those in a nanoelectronic device, can melt. Many materials can’t currently be used to make sensors because they can't withstand heat,” Nasiri said.

However, the new technique bypasses this heat-intensive process, allowing nanosensors to be made from a broader range of materials. Adding one droplet of ethanol onto the sensing layer, without putting it into the oven, will help the atoms on the surface of the nanoparticles move around, and the gaps between nanoparticles disappear as the particles join to each other. “We showed that ethanol greatly improved the efficiency and responsiveness of our sensors, beyond what you would get after heating them for 12 hours,” Nasiri said.

The new method was discovered after the study’s lead author, Jayden (Xiaohu) Chen, accidentally splashed some ethanol onto a sensor while washing a crucible, in an incident that would usually destroy the sensitive device. “I thought the sensor was destroyed, but later realised that the sample was outperforming every other sample we’ve ever made,” Chen said.

Nasiri said that while the accident may have given researchers the idea, the method’s effectiveness depended on painstaking work to identify the exact volume of ethanol used. “When Jayden found this result, we went back very carefully trying different quantities of ethanol. He was testing over and over again to find what worked. It was like Goldilocks — three microlitres was too little and did nothing effective, 10 microlitres was too much and wiped the sensing layer out, five microlitres was just right!” Nasiri said.

The researchers have tested the new method with UV light sensors, and also with nanosensors that detect carbon dioxide, methane, hydrogen and more — the effect is the same, according to Nasiri. “After one correctly measured droplet of ethanol, the sensor is activated in around a minute. This turns a slow, highly energy-intensive process into something far more efficient,” Nasiri said.

Novel biosensor increases element extraction efficiency

Biologists have developed a novel biosensor that can detect rare earth elements and could be...

Making sensors more sustainable with a greener power source

A new project aims to eliminate the reliance of sensors on disposable batteries by testing the...

Fission chips — using vinegar for sensor processing

Researchers have developed a new way to produce ultraviolet (UV) light sensors, which could lead...