UNSW opens e-waste microfactory

UNSW Sydney has opened a microfactory that can transform the components from electronic waste (e-waste), such as discarded smartphones and laptops, into valuable materials for re-use — an intiative that is claimed to be a world first.

A microfactory is one or a series of small machines and devices that uses patented technology to perform one or more functions in the reforming of waste products into new and usable resources. UNSW’s modular microfactory can operate on a site as small as 50 m2 and can be located wherever waste may be stockpiled.

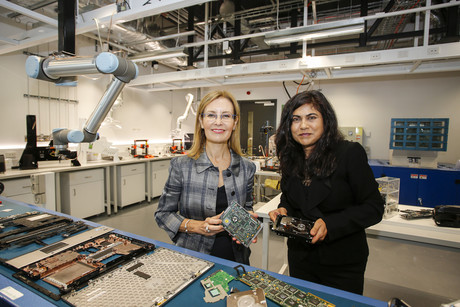

Using technology developed following extensive research at UNSW’s Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT@UNSW), the e-waste microfactory has the potential to reduce the rapidly growing problem of vast amounts of electronic waste causing environmental harm and going into landfill. It was launched today by NSW Minister for the Environment Gabrielle Upton, who described it as a “home-grown solution to the waste challenges facing communities all over the world”.

“It is exciting to see innovations such as this prototype microfactory and the potential they have to reduce waste and provide a boost to both the waste management and manufacturing industries in NSW,” Upton said.

So how does it work? The microfactory has a number of small modules to handle discarded electronic devices such as computers, phones and printers. The devices are first placed into one module to break them down, while the next module may involve a special robot for the identification of useful parts. Another module makes use of a small furnace which transforms these parts into valuable materials by using a precisely controlled temperature process.

These transformed materials include metal alloys, such as copper and tin, and a range of micromaterials. The micromaterials can be used in industrial-grade ceramics, while plastics from computers, printers and other discarded sources can be put through another module that produces filaments suitable for 3D-printing applications. The metal alloys can meanwhile be used as metal components for new or existing manufacturing processes.

According to Professor Veena Sahajwalla, director of SMaRT@UNSW, the e-waste microfactory is the first of a series of microfactories under development at UNSW that can also turn many types of consumer waste streams — such as glass, plastic and timber — into commercial materials and products.

“Our e-waste microfactory and another under development for other consumer waste types offer a cost-effective solution to one of the greatest environmental challenges of our age, while delivering new job opportunities to our cities but importantly, to our rural and regional areas, too,” Professor Sahajwalla said.

“Using our green manufacturing technologies, these microfactories can transform waste where it is stockpiled and created, enabling local businesses and communities to not only tackle local waste problems but to develop a commercial opportunity from the valuable materials that are created.”

Professor Sahajwalla said microfactories offer a truly sustainable solution to the growing waste problem, proving you can transform just about anything at the micro-level and transform waste streams into value-added products. “For example,” she said, “instead of looking at plastics as just a nuisance, we’ve shown scientifically that you can generate materials from that waste stream to create smart filaments for 3D printing.

“These microfactories can transform the manufacturing landscape, especially in remote locations where typically the logistics of having waste transported or processed are prohibitively expensive. This is especially beneficial for the island markets and the remote and regional regions of the country.”

UNSW developed the technology with support from the Australian Research Council and is now in partnership with a number of businesses and organisations, including e-waste recycler TES, mining manufacturer Moly-Cop and spectacle maker Dresden Optics. Ultimately, the challenge is to commercialise and create incentives for industry to take up this technology — and to change behaviour — as societies and communities around the world seek to be more sustainable.

Originally published here.

Electronex Sydney a major success

More than 1000 trade visitors and delegates have attended the Electronics Design & Assembly...

Gartner: Global AI chips revenue to grow 33% in 2024

Gartner has forecast that the revenue from AI semiconductors globally will total $71 billion in...

Electronex Expo returns to Sydney for 2024

Electronex — the Electronics Design and Assembly Expo will return to Sydney in 2024,...